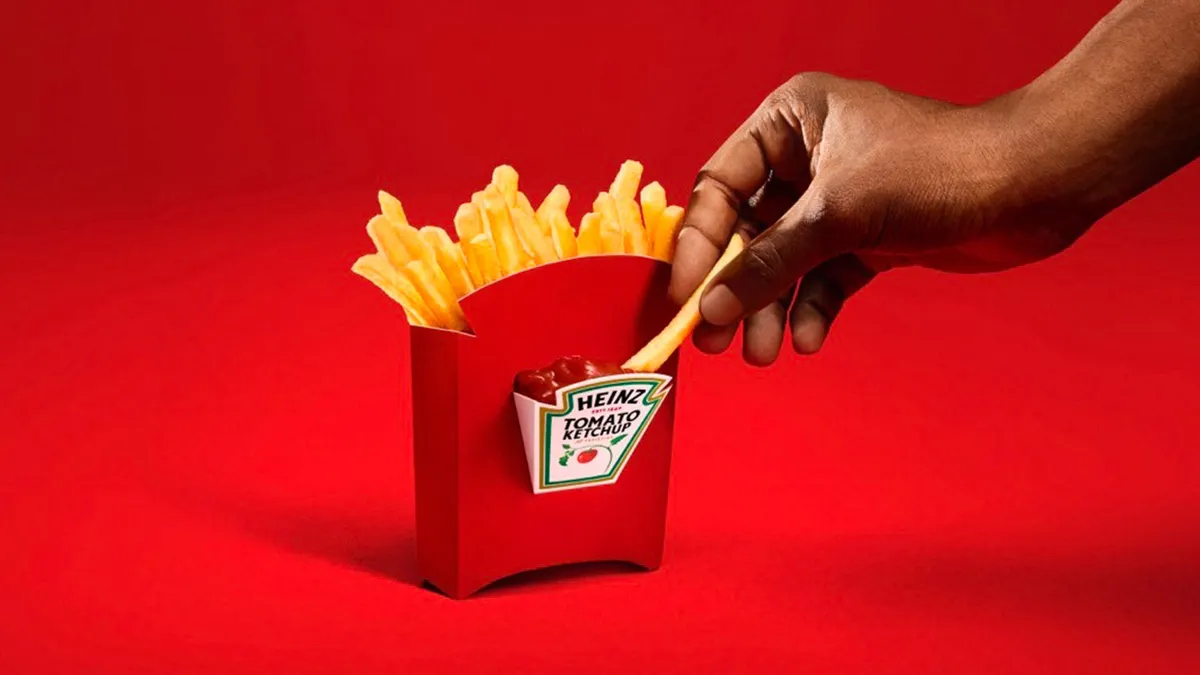

Black rigid plastic is a familiar packaging substrate in the United States, used to manufacture the likes of takeout food trays, to-go coffee cup lids and cosmetics tubs. What happens to those items at their end of life is less understood by the public, but has long caused many brands, recyclers and packaging manufacturers to consider the material a black sheep.

While materials accepted for recycling vary regionally, it's a nearly universal truth that black rigid plastics are not accepted in U.S. residential recycling streams. The color designates the material as largely unsortable with standard equipment.

“People that are putting black plastic in the recycling bin just kind of think that it's plastic, so it's going to get recycled. But most MRFs across the country are not identifying black,” said Jeff Snyder, senior vice president of recycling and sustainability at Rumpke Waste & Recycling.

A typical U.S. materials recovery facility’s optical sorters with near-infrared sensors can't distinguish black packaging items from the dark conveyors they travel on through sorting lines, said Brent Bell, vice president of recycling at WM. Optical sorters became mainstream in the last five years, and they're only now being equipped with technologies like lasers and artificial intelligence to effectively identify black plastics.

“The sortability of black plastic today has come a long, long way from even three years ago,” Snyder said.

MRF upgrades to sort black plastics mark a milestone, operators say, and raise optimism that the material could get bumped off recycling blacklists. Progress isn't fast, though, and some brands and manufacturers have instead opted to redesign packaging without black plastics to improve recyclability.

Sorting difficulty isn't the only factor that has made black plastic packaging a recycling pariah. Recyclers also heavily weigh the color of money: MRF operators still don't view the material as a profitable commodity due to a lack of end markets.

“I believe I can sort it” at Rumpke’s new MRF in Columbus, Ohio, that opened in August 2024, Snyder said. “But I also believe that the end markets don't want it."

Markets for all recovered plastics have been depressed for years, but black and mixed-color polyolefins have especially taken a hit, according to Emily Friedman, recycled plastics senior editor at commodity intelligence service ICIS.

“The mixed-color materials really don't get the same kind of love [as natural],” she said. “In today's market, we are at the absolute floor for these mixed-color resins.”

Further complicating the picture is that solid data on the prevalence of black plastics in recovered commodity markets is not readily available, making for a murky view about whether the tide is indeed turning on the material’s acceptance in recycling programs. Sources agree that black rigid plastic packaging recycling is at a tipping point – it's just a matter of determining which way the chips will fall.

Carbon black eye

Black rigid plastic packaging used in the United States typically is manufactured from polypropylene, polyethylene, polyethylene terephthalate or polystyrene. While non-black packaging made from the first three polymers is commonly accepted in curbside recycling programs, PS is not.

Manufacturers historically viewed black as a desirable color option for plastic packaging considering “it definitely hides flaws,” said Jonathan Quinn, CEO of the U.S. Plastics Pact, referencing nearly two decades of experience in the plastic packaging industry. “They're able to buy off-spec, wide-spec material at a significant cost reduction and throw a little black in it. And the color matching on black is pretty easy.”

Problems arise, however, when trying to give those plastics a second life.

Carbon black, the main pigment, is what gives the material a black eye. Carbon black is considered to be a respiratory irritant and potential carcinogen in its raw form, according to the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, and it hinders recycling when incorporated into packaging. Carbon black is on the list of problematic and unnecessary materials that USPP participants aim to eliminate from packaging by 2030.

“When problematic materials find their way into the recycling stream, it causes detriment to performance of those recycled materials and contaminates the recycling stream,” Quinn said. “And when you look at the desire and the need to incorporate more recycled content, we have to continuously strive to create a cleaner stream and a consistent stream – and that's a very complex situation.”

Carbon black also comes up in Oregon's extended producer responsibility for packaging law, which in July became the first of seven similar state laws to take effect. In general, sources expect EPR for packaging laws and minimum recycled content regulations to boost recycled resin markets. But it’s too soon to know if these policies will change the fate of black plastic, even as recyclers invest in new technologies that are increasingly capable of capturing the material.

Back in black?

Equipment manufacturers frequently tout the benefits of optical sorters’ near-infrared sensors, some pointing to black plastic detection capabilities. Yet the Association of Plastic Recyclers does not consider NIR a reliable technology to sort black plastics, according to a report it first released in 2018 and most recently updated in October 2024. The carbon black absorbs many NIR wavelengths rather than reflecting them, making black plastic undetectable to the system, the report says.

Equipment manufacturers are introducing machinery that instead uses mid-infrared spectroscopy to identify plastics that contain carbon black. Manufacturers including Tomra and Specim say their MIR-enabled equipment provides higher resolution and greater specificity than other technologies.

The few U.S. MRF operators that have installed technologies capable of detecting black packaging say it's still only for pilot programs. That's the case for WM, which added this equipment during a $39 million upgrade at its MRF in Germantown, Wisconsin, that reopened in January 2024.

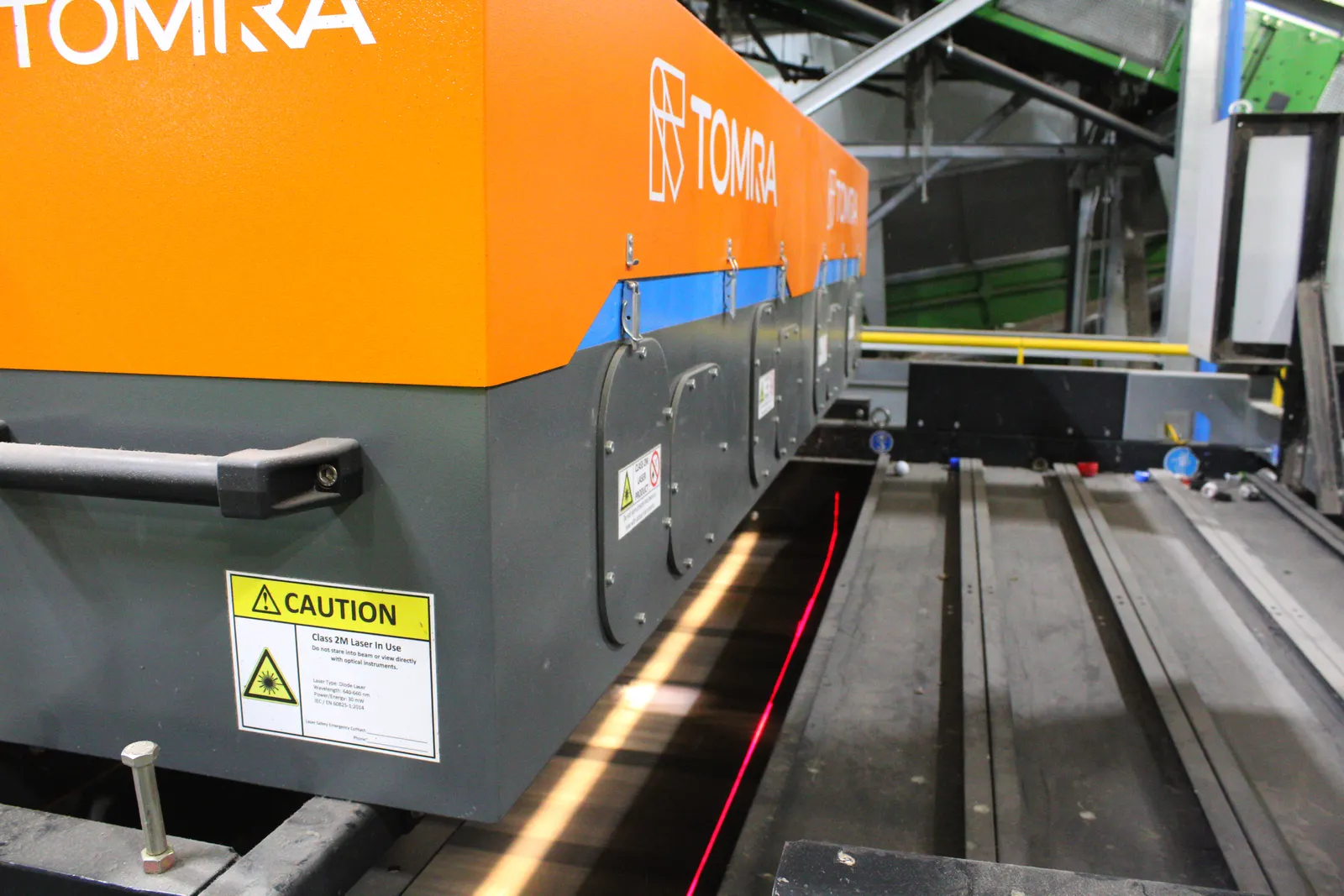

WM installed the Tomra Autosort optical sorter, which has laser beams to aid with material identification in addition to light and camera features. Most of the new optical sorters that WM is installing during its $1.4 billion nationwide investment cycle from 2022 to 2026 will incorporate laser object detection, Bell said.

"I think as long as we keep on seeing the success we see in Germantown [and other] locations, we'll continue to expedite and invest in the other facilities so they can capture that material as well," said Bell.

The Autosort's NIR sensor detects non-black materials, while LOD senses an object's height by measuring the displacement of the laser line, said Valerio Sama, business development manager for packaging at Tomra Recycling, via email.

When an object containing carbon black passes through this sensor combination, “the laser confirms that there is indeed an object on the belt, while the NIR does not provide any signal because it cannot detect black. Based on this exclusion principle, the classification system concludes with high probability that the object must be black," Sama said.

Machinex optical sorters do not use lasers, explained CEO Chris Hawn, but they do incorporate another emerging technology that could be used to detect black plastic: AI. Machinex representatives visited Rumpke's Columbus MRF in August to run various system tests, including on the ability to capture black plastics.

"We have not been marketing it yet. We first wanted to see what our purities and efficiencies were," Hawn said. Although testing is in the early stages, trials are producing recovery rates of 85% or greater. "After the numbers I've been given, I can say comfortably that we can remove black plastics from the stream and direct them to their own bunker," he said.

The Machinex technology isn't yet able to identify black plastics by discrete polymer, but that is on the docket, Hawn said. Similarly, Tomra's MIR-enabled technology cannot yet distinguish between polymers, Sama said.

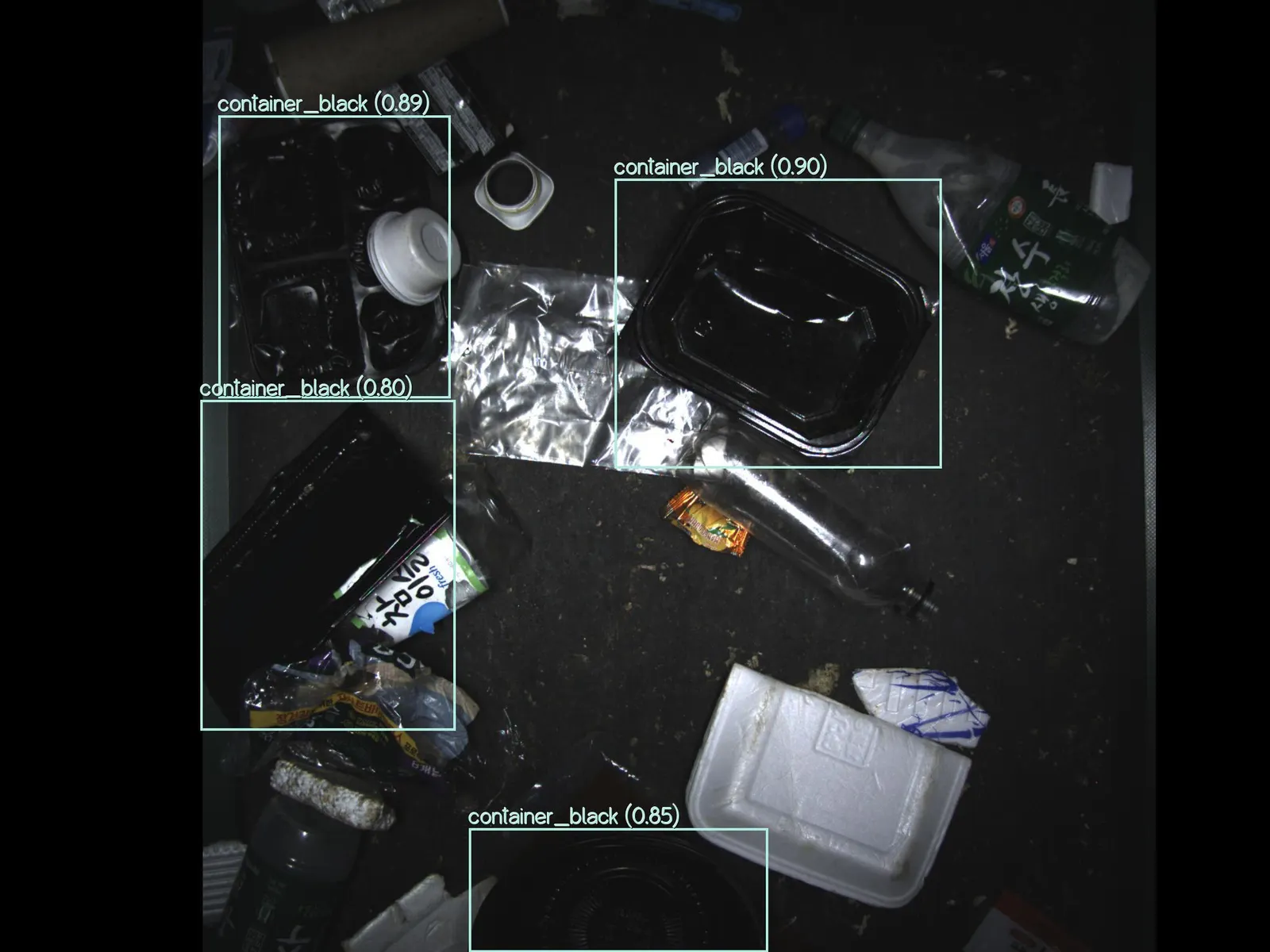

The same is true for waste analytics equipment vendor Greyparrot’s technology, said Chief Operating Officer Gaspard Duthilleul. That technology is based on computer vision and powered by AI, with the vision system providing the main difference from NIR-enabled optical sorters to enable black plastics identification, said Duthilleul. "Things have evolved quite a lot, actually, in the past three years."

The vision system integrates with MRFs' sorting lines and analyzes streams, and the portal provides operators with data about specific materials. The system can determine which items are being captured and which are heading to disposal.

"Black plastic is, for sure, one of the main packaging [types] which is being lost," Duthilleul said.

In 2024, 55% of the black plastic packaging that Greyparrot's technology detected, by mass, showed up in residue lines bound for disposal instead of being captured for recycling. Black plastics were 3.3% of the total tonnage of residue analyzed on MRF conveyors. They represent more than 15% of all recyclable plastic the company analyzes.

More work is needed across the value chain for black plastic packaging to become a desirable commodity to capture, said Duthilleul. In June, his company launched a new platform, Deepnest, to help that by providing consumer packaged goods companies and other brands with data about what happens to their packaging once it reaches recycling streams.

The data offers insight into what packaging is being captured, with information about product type, material, region and brand. The platform aims to "solve this problem of miscommunication and misunderstanding between the brands and the waste management," and the insights generated can be used to improve packaging designs, Duthilleul said. For instance, the findings might prompt a brand to decrease the amount of carbon black in a packaging item so it can be captured for recycling.

Greyparrot's technology is deployed in 55 waste and recycling facilities in 20 countries, with about 20% of business coming from U.S. facilities. The company began its push into the U.S. early last year and considers it a growth market, Duthilleul said. However, black plastic identification hasn't been a major draw for customers so far, he said, beyond one in South Korea that incorporates the material into mixed plastic bales.

Similarly, Machinex hasn't noticed a clear uptick in customer demand for its equipment to sort black plastics, although Hawn said "people are asking questions [about it] a little bit more."

Tomra has experienced limited demand for sorting equipment with black plastic capabilities in Europe because that packaging is “gradually disappearing from product ranges" there, Sama said. Based on black packaging’s prevalence in the United States, the company specifically made its MIR spectroscopy-enabled system to meet U.S. customers' demand.

Fade the black

Despite enhanced efforts to recycle black plastics, certain brands, packaging manufacturers and recycled resin manufacturers instead are lightening up their plastic packaging hues to improve circularity.

This year, Sam's Club tweaked the design for its rotisserie chicken clamshells, with bottoms made from food packaging manufacturer Sabert’s proprietary PP blend that contains 25% PCR. The "stone color" makes the base easier to recycle than the previous black version, the companies say.

In June, Amcor announced a partnership with French food company Cofigeo Group for a single-serve, three-compartment meal tray made from multilayer PP. It’s manufactured in a near-infrared terracotta masterbatch, instead of black, for easier detection at MRFs.

In 2024, Walgreens disclosed its work to switch the color of bottle caps from black to white on its own-brand product packaging to improve recyclability. SC Johnson did the same this year with the caps on its Mrs. Meyer's brand cleaning products.

Colorant companies are getting in on the action, too: Ampacet and Chroma Color are among the suppliers transitioning toward carbon black alternatives. Plus, PCR producers are fading the black.

“What we're already seeing today is those recyclers who traditionally have produced a postconsumer black resin are now adding equipment to be able to provide color-sorted materials,” said ICIS' Friedman.

Many dabble in colors that can be commonly used, such as grays and whites, while some experiment with bolder hues like red-orange-yellow or blue-green-black, she said. "This, of course, is an attempt to incentivize brands to use PCR and to say, 'Hey, your package is already this color. You could use this potentially instead of natural.'"

Transitioning to detectable pigments can come with extra costs, said USPP's Quinn, noting the low price of black recovered resins compared with natural or lighter hues. "It's a constant balancing act," he said.

Conversely, some brands are finding new ways to incorporate black into their plastic packaging portfolios. Cost pressure plays a role, Friedman said, as do certain applications where color doesn't matter or a shrink sleeve might be added over the packaging.

"We're seeing more and more of that," she said, while clarifying that "it's not a massive wave of demand. It is a trickle of companies on this development path, learning journey, who are making those types of transitions."

Meanwhile, MRF operators report that they’ll continue to invest in equipment capable of sorting black plastics for the time being, because they haven’t observed notable differences in the volumes of the material flowing into their facilities despite some brands’ color switches.

Black markets

A lack of dependable end markets has long held back MRF operators from launching full-scale black plastics collection programs.

"The ability in our industry to sort black plastic is there, but the acceptability from the folks that buy polypropylene and PE is not there," said Snyder. "So I am not going to go public yet and tell everybody, the Rumpke customers, to put black plastic in the recycling bin."

Market challenges preceded the barriers with optical sorters, sources say. Recovered resin markets are tied to virgin resin markets, and the lack of demand for recovered is pulling down its price, said Friedman.

"With how cheap virgin plastic is, it really disincentivizes the purchase of mixed-color or black material," Friedman said. "We're talking about low single-digit cents per pound feedstock pricing, with recyclers who are running out of storage space because their inventory is so high because demand has been so weak.”

During the last five years, a wave of virgin resin production capacity has emerged globally, much of it in the United States or Canada. With that comes oversupply, resulting in virgin's "intense price competition" with recycled resins, Friedman said. Plus, geopolitical factors including economic uncertainty due to tariffs have further pulled down end market demand in 2025, she said.

ICIS doesn't project that markets will improve much in the next couple of years. "We would need widespread global rationalization of virgin capacity, and that's going to take time," Friedman said.

Some recovered material purchasers accept only a limited amount of black items in mixed rigid plastic bales, sources say. MRF operators question whether buyers are willing to procure entirely black bales — and consume the volume of material that would enter their facilities.

KW Plastics is one of the few consistent consumers of MRFs' recovered black rigid plastic packaging. The company processes the recovered black polypropylene and high-density polyethylene material into plastic flake, then extrudes plastic pellets; the majority are black, but some batches are gray, said General Manager Scott Saunders.

Manufacturers use KW's postconsumer recycled plastic resins to make products such as paint buckets, garden pots and automotive components, including battery cases. Durable industrial goods, a category that includes pipes, crates or engineered lumber, is one of the only viable end markets for the recovered material.

"Black plastic is not usually going back into new packaging," USPP's Quinn confirmed.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration maintains a narrow spectrum of plastics allowed to be used as PCR for food-contact applications. It still does not permit recovered black plastics under the umbrella — even though a large proportion of the material originates from food service packaging.

KW must ensure black material is segregated from lighter material, Saunders said. The company consumes nearly 100 million pounds of black postconsumer resins each year. While much of the material it receives is in mixed bales, in August the company tested bales composed entirely of black plastics to determine how much is recoverable.

"The color is not a problem, as long as that black material is not full of calcium carbonate or fillers," Saunders said. Black PP used for certain packaging, such as rotisserie chicken clamshell bottoms, incorporates calcium carbonate to aid heat distribution, "but it changes the bulk density of the plastic to where in a wash line it'll sink and come out in the trash," he said.

Banking on black magic

While open market factors such as MRF upgrades, brand redesigns and commodity market movement play out, policy could end up forcing action on black plastic packaging in the future.

"I wouldn't say that [EPR] has grown our market as of today. But it certainly has brought more interested parties to the marketplace to test material, to make sure they have a strategy for 2030 when these EPR requirements start kicking in," said KW Plastics' Saunders.

Similarly, a lot of the testing that Machinex performed at Rumpke’s Columbus MRF was related to EPR, Hawn said.

But PCR mandates might not benefit black plastics, cautioned ICIS' Friedman. "The EPR incentives to use recycled resins, they're going after the natural or the clear recycled resins, not the mixed color or the black."

Plus, PCR minimums often relate to food packaging, she said, a market in which black recycled plastics aren't a player. The mandates typically specify material must be "postconsumer," not "postindustrial," which creates an additional impediment for black plastics. Going forward, more opportunities for natural recycled resins, and fewer for colored, are likely, Friedman said.

Such disparities underscore sources' calls for a little black magic, in the form of greater collaboration across the value chain, to improve the design and end-of-life options for black plastics.

“I'm personally quite passionate about this kind of systemic approach to it," said Greyparrot's Duthilleul. "You can improve waste management as much as you want. But if you don't change the way things are designed, if you don't enable this communication and this systemic thinking – from the brand, from the packaging producers, from the recycler – then you won't actually solve the problem.”