Many California schools count on Revolution Foods for millions of meals annually. But the food service company got an earful from students within the San Francisco Unified School District last year — not about the food itself, but the trays on which it was served.

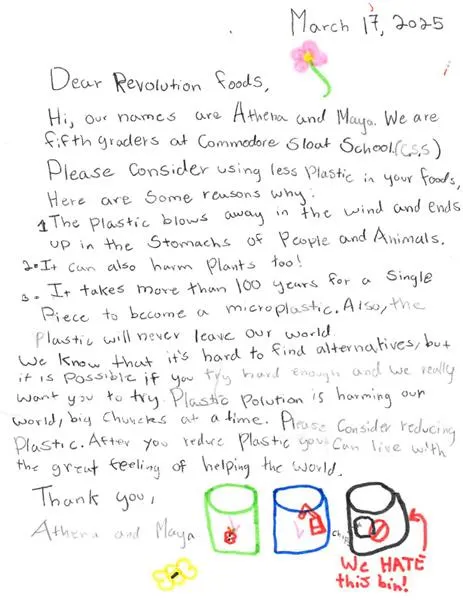

“We had three different student advocacy groups reach out to us to question what we could do to help them reduce plastic across their campuses,” explained Senior Marketing Director Heather Clevenger.

She learned that a few years earlier, Revolution had looked into using compostable materials to replace the single-use PET trays most of its meals were served in. But the company dropped the idea due to high costs and performance concerns.

Seeing renewed interest and growth in the compostable packaging market, Clevenger has spearheaded another effort. The company recently launched a pilot project across the 95 schools it serves in San Francisco, testing a compostable molded fiber food tray made from bagasse with a liner made of polylactic acid, or PLA.

In its 2025 research report on disposable service ware, the Freedonia Group predicted that molded fiber would see strong growth thanks to its use in compostable packaging and because it can be made from waste biomass. Overall, the global compostable packaging market was worth $56 billion in 2024, with some estimates pegging it to reach $90 billion by 2032. Emerging packaging circularity policies, including state extended producer responsibility laws in California and elsewhere, are one catalyst.

Yet a variety of factors still cloud this segment’s future, including still-developing — and in some cases, contradictory — regulations. Some concerns remain regarding compostability claims, as well as uncertainties about feedstocks and material capabilities. The National Organic Standards Board, which advises the U.S. Department of Agriculture on organic standards, has also held off on endorsing compostable plastics as compost inputs.

The long view

Before replacing incumbent materials, companies like Revolution need to ensure that compostable alternatives will perform comparably well. That’s especially true for service ware, where food safety and functionality are key. Clevenger said that when selecting a tray for the school lunch pilot, she focused on the PLA liner.

“The minimum threshold was that we could find a tray that functioned similarly to its plastic counterpart,” said Clevenger. That includes holding acidic foods, such as spaghetti sauce, and remaining leakproof through the journey from the production kitchen through transport to a school in insulated carriers, and then through food service.

Before initiating the pilot project, she and her team ran a range of compostable containers through a battery of tests with different types of foods. Kids eat with their eyes, she said, so something like oil leaking through and staining the exterior of the tray could deter them and lead to waste, let alone hungry kids.

Bill Orts is research director at the USDA Bioproducts Research Laboratory near Berkeley, California. He’s worked with multinational corporations including Clorox and Coca-Cola and compostable packaging companies such as World Centric. He’s watched many products, like the trays Revolution is testing, evolve from ideas sketched on whiteboards to packaging products on store shelves, in food service and in consumers’ homes.

Orts takes a long view of the compostables packaging sector. When it comes to competition with traditional plastics, “the petrochemical industry had a hundred-year head start,” he said. But despite that uneven playing field, bioplastic companies are improving their market share and growing the infrastructure needed to compete with conventional plastic packaging. Consumer demand is a big driver for that, he said.

The packaging’s end of life was another important consideration for Revolution. The student environmental advocates made it clear that they want schools to move away from single-use plastics.

Clevenger says Revolution has confirmed that Recology, the city’s organics waste hauler, accepts the molded fiber tray and its PLA liner. Yet there are questions about how various regulatory decisions could influence acceptance in California in the future.

California’s composting conundrum

The state’s packaging EPR law, SB 54, requires that all single-use packaging and plastic food ware must be recyclable or compostable by 2032. But another statute, AB 1201, requires that products labeled “compostable” and sold in the state must be in accordance with the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Organic Program. And that program disallows compost inputs made of bioplastics, such as PLA and other synthetic materials, regardless of whether they are certified as compostable.

In 2025, CalRecycle, the state agency charged with implementing both laws, extended the AB 1201 compliance deadline to June 30, 2027. At its annual fall meeting, the National Organic Standards Board was set to vote on whether compostable plastics should be allowed as compost inputs. The meeting was postponed due to the government shutdown and was rescheduled for Jan. 13-14 as a virtual meeting.

Meeting materials posted to the USDA website, including a technical review that the board commissioned, indicate that the NOSB would likely not vote in favor of recommending that the National Organic Program allow compostable packaging as a feedstock.

Allison Johnson, a senior attorney with the Natural Resources Defense Council and NOSB member, told Packaging Dive that the technical review leaves open the possibility of allowing compostable packaging on a material by material basis, rather than a categorical allowance.

Johnson sits on the subcommittee of the NOSB that requested the technical review last year in response to a petition that the Biodegradable Products Institute filed with the USDA in 2023. In it, BPI argued that the Organic Foods Production Act of 1990 classifies compost as non-synthetic. It also states that in an industrial composting process the bioplastic material used in BPI-certified compostable packaging biodegrades into elements that are indistinguishable from the resulting compost. Including compost feedstocks in the national list, therefore, is inconsistent with congressional intent, it argued.

In response, the National Organic Program asked the NOSB to review the petition. The NOSB disagreed with BPI’s argument and requested the technical review.

“There have been a range of perspectives on this issue on the [NOSB], and so it was very helpful to have the technical review because now we have a neutral assessment of the underlying facts and where the science is. And that kind of grounds everyone in the same information,” said Johnson, speaking on behalf of her role on the standards board.

But Rhodes Yepsen, executive director of BPI, which works with brands to set and issue a compostability certification for packaging, rebutted that the technical review includes “some serious technical and scientific issues, some glaring errors in omissions,” and therefore should be withdrawn.

Islands in the stream

Because organic farms cannot currently use compost made from inputs that include compostable packaging, some composters do not accept the material for processing at all. Others have developed dual streams: one for conventional compost in which they allow compostable packaging, and a second feedstock stream that does not. Meanwhile, for composters that do not sell organic-certified compost, the decision to accept compostable packaging might just come down to whether they see value in doing so.

Compostable polymers have become a polarizing issue among compost producers. In August, a coalition of composters published a letter countering some of the arguments against the acceptance of certified compostable packaging, such as concern that it does not fully biodegrade, or that accepting it also increases non-compostable contaminants in compost feedstock.

The letter was an attempt “to bring balance to the conversation,” said its author David Paull, chief impact officer at Compost Now, which provides composting services. Paull acknowledged that producers on the West Coast, particularly in California where mandates have resulted in significant increases in collected organics, have seen increased contamination from non-compostables.

“I think, unfortunately, compostable packaging has kind of been lumped into that conversation,” he said, with many in the industry thinking “it's just a part of the problem.” While he allows that accepting compostable packaging “can be operationally challenging,” he believes it can also be managed well if systems are designed well.

Compostable packaging’s role in EPR is TBD

The growth of the compostable packaging sector, municipal composting programs and regional composting mandates has raised questions over whether and how composting should be included in extended producer responsibility laws. The seven states that have adopted EPR laws thus far have not addressed compostable packaging consistently, adding another layer of complexity for companies that use or plan to use it.

While neither Oregon nor Maine explicitly included support for composters and compostables in their laws, other states did. But how the materials are defined varies, as do elements such as fee structures, education and infrastructure investments.

Paul Nowak, the executive director of GreenBlue, told Packaging Dive last fall that the organization’s member companies are focused on recyclability and conventional packaging, for which EPR laws have more developed targets and cost structures.

For now, he said, recyclability is getting “all of the air in the room.” But he expects that to change once companies have maximized their efforts around product recyclability and recycling systems. “I do feel you will see composting start to come back up as a solution,” he said.

The Sustainable Packaging Coalition recently analyzed composting access in the largest U.S. cities accounting for roughly 60% of the national population. It found that nearly 18% of residents in those areas had access to curbside or drop-off programs that accept food waste only, while just over 18% had access to curbside or drop-off programs that accept some form of compostable packaging in addition to food waste.

If Nowak’s projection proves accurate, composting infrastructure will need to grow. That could be through more curbside collection programs, drop-off systems or take back programs.

But Orts offers a more radical vision, which he said is taking root in some European countries: moving away from single-use, non-compostable plastics altogether. “So no more single-use plastic unless it's fully compostable or fully reusable,” he said.

Jennifer LaBarre, executive director of the San Francisco Unified School District’s Student Nutrition Services, said the district is interested in reusable service ware. But many of the schools lack kitchens with adequate storage and washing infrastructure, making logistics of reusable service ware complicated.

She said that while compostable packaging addresses environmental concerns about single-use plastics, it’s not ultimately what she’d like to see. “If we can move to real plates, those different types of things, that's really where our goal is,” she said.

For now, Revolution Foods’ Clevenger is focused on testing the compostable food trays, hoping the product earns good grades for performance. She added that the packaging vendor involved in the pilot, which she declined to name, is closely tracking CalRecycle’s efforts to work out conflicts between the state’s EPR law and AB 1201. The result will impact whether Revolution and compostable packaging producers that integrate bioplastics into their products will even be able to serve customers in the Golden State.

Clevenger hopes compostable packaging will remain an option for Revolution, and that it will continue to improve and become more affordable as the sector scales. “As more options come to the table, we will absolutely be taking a critical look at every piece of material that's in our meal service solution,” she said.