Stress levels are high for CPG companies and packaging groups as extended producer responsibility programs unfold in multiple states.

This was on display at three recent Boston events hosted by the Sustainable Packaging Coalition, How2Recycle and the Northeast Recycling Council, with questions flying about costs, policy harmonization and relationships with regulators.

Paul Nowak, executive director of GreenBlue, adopted the role of support group leader for a room full of representatives from many of the world’s largest CPG companies in his opening talk at SPC Advance. He reminded them that “you are not alone” and urged them to take the long view on this major industry shift.

“What you see at the end of the change is not what you see during the change,” said Nowak, drawing on examples from prior industry shifts as well as other major life events. “You are in this uncomfortable period right now where it's not moving as rapidly as you would think and you don't have the historic perspective yet of where it could go.”

Sticker shock

While CPGs are familiar with EPR costs from programs in other countries, the complexity and scale of the U.S. rollout in seven states is presenting its own unique challenges.

Oregon is the only state that’s begun collecting fees, and already the costs are high. Circular Action Alliance, the producer responsibility organization selected for the majority of state programs to date, estimates a budget of $188 million in the program’s first year, with that figure growing in the years ahead.

Charlie Schwarze, board chair for CAA and senior director of packaging stewardship at Keurig Dr Pepper, said the costs are starting to resonate with major companies. KDP, for example, has been working to sort out different aspects of its packaging in terms of licensing arrangements, private label manufacturing partnerships and other factors. This requires a close relationship with the company’s finance, R&D and procurement teams to gather data and make cost projections.

“It's been a bit of a slow-moving process because the dollars, at least in 2025, are not extremely notable. But they're going to get bigger pretty quickly,” he said, citing Colorado and California’s programs on the horizon.

Shane Buckingham, chief of staff at CAA, said it will be months until companies have a better sense of the true costs. The group set initial fees for California, which won’t be invoiced until August 2026, but those fee levels are expected to change once SB 54 regulations are finalized.

“Please don't take our early fee schedule of being indicative of what your cost will be in 2027, it's just a drop in the bucket,” he said. "The fees are going to go up significantly in California because we have to fund a $500 million [plastic] mitigation fund, we're going to have system funding to improve recycling, source reduction, reuse, refill.”

SPC Director Olga Kachook encouraged attendees to think about these fees as motivation to innovate rather than a burden. In her view, avoided fees through ecomodulation could be viewed as “possible new investment capital” for covering the costs of material switches, R&D, MRF testing, consumer education campaigns and more.

“We can innovate to those lower fees by switching to incentivized materials and formats and then we can reinvest the savings back into sustainable materials and infrastructure that seemed out of reach,” she said.

Searching for harmony

All three events also featured ample discussion about if or how aspects of current EPR programs could be better aligned. While regulators are working to align certain definitions where possible, they also noted that certain state programs were uniquely designed for a reason.

David Allaway, senior policy analyst at the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality, said during NERC’s Rethink Resource Use Conference that he sees a potential benefit to harmonizing ecomodulation approaches in some cases. But at the same time, he said, “I fear that the push for harmonization will lead to a race to the bottom” by potentially limiting the ability for states to craft policies based on their respective needs.

As for those who critique other unique aspects of Oregon’s law, such as responsible end market requirements, Allaway said “that’s not negotiable for us,” as market issues were a leading motivation for the law in the first place.

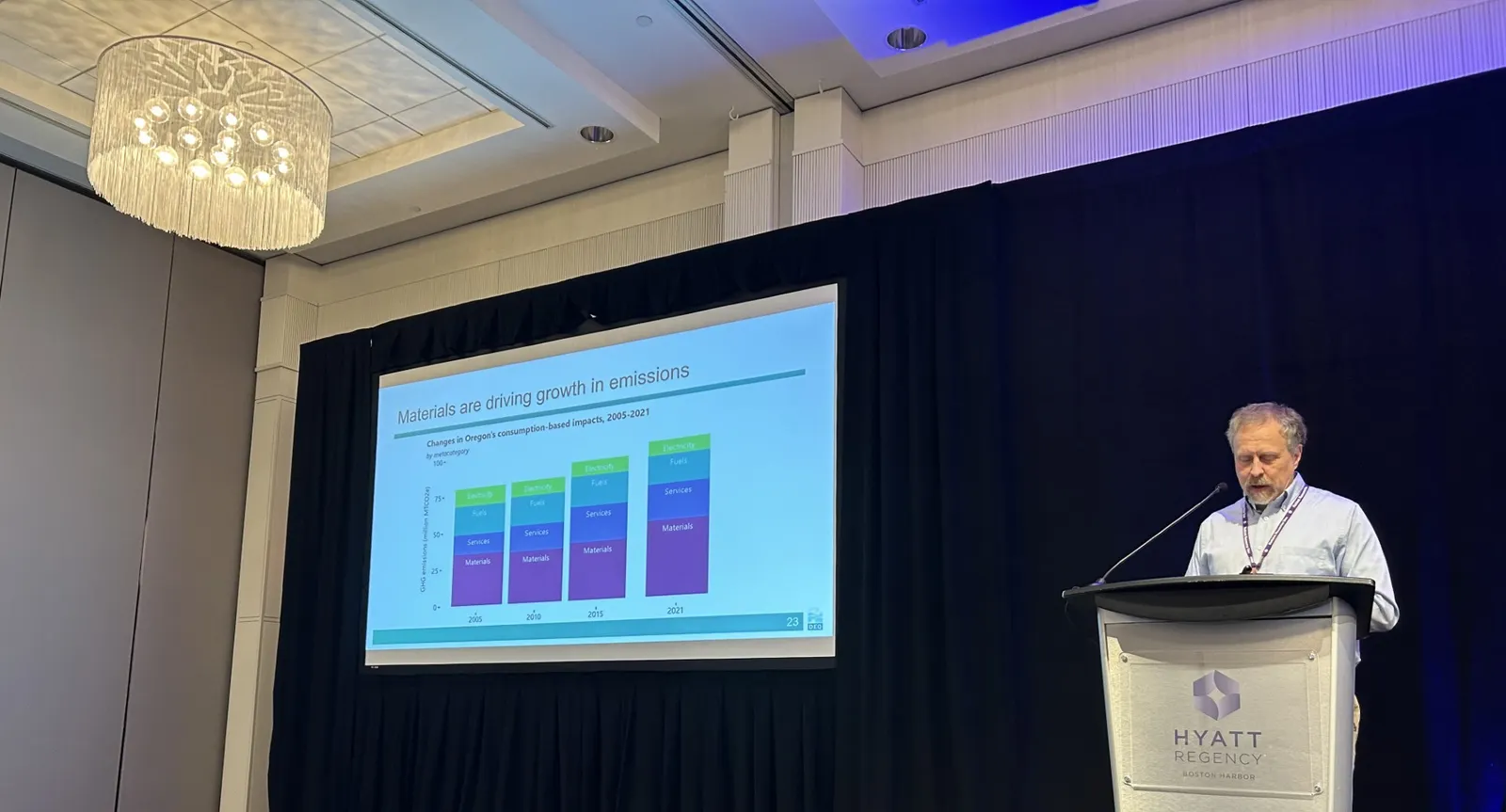

Allaway said Oregon’s system was established based on specific regional priorities, such as putting an end to exporting certain types of material that led to dumping in other countries. The state’s approach to ecomodulation and life cycle analysis is also informed by years of work on greenhouse gas inventories and consumption-based accounting, which challenges many commonly held assumptions about recyclability.

Each state has its own unique factors in terms of collection access and market infrastructure. Colorado, for example, has many areas that will be getting recycling service for the first time. Maine also has many rural areas that previously had access to recycling but lost it in recent years. Meanwhile, in Maryland, collection service may be more common but local end markets are lacking for certain commodities.

Jason Bergquist, vice president of consulting firm RecycleMe, said during the NERC event that he hears concerns from clients about where this is all headed.

“If we get to a couple years down the road and we’ve got, let’s just pretend, 25 states with EPR, with different deadlines, different [covered material] lists, different definitions, different ecomodulation — my concern as a fan of EPR is that the pushback will be so significant that it could get existential for the producers,” he said, in terms of costs and compliance management.

At the same time, Bergquist said the experiences of packaging EPR in Europe and Canada show it may take years to get toward any kind of harmonized system.

Back at SPC Advance and the co-located How2Recycle Summit, California loomed large throughout the week when it came to these questions.

Karen Kayfetz, chief of CalRecycle’s product stewardship branch, said regulators from different EPR states try to talk to one another as much as possible but in some cases they’re limited by the statutes that created these programs.

“We each have our own legal frameworks we have to work within,” she said. “So harmonization starts with the legislatures, and that is not our responsibility, but it is something that we could see change and evolve over the coming years.”

As all of these complex questions get worked out, Kayfetz reminded attendees that CalRecycle may currently be “the face” of the program but that’s not the long-term goal.

“What would make me the happiest is if you leave here thinking ‘let’s go talk more to CAA.’ Because EPR is a policy mechanism that is meant to be a public-private partnership where the public entity ... is overseeing the PRO,” she said. “They are your partner and we are their police.”

In a separate session, CAA’s Buckingham described the work of ramping up different state fee and reporting programs as building a plane while flying it. The group is working to streamline its own reporting processes as much as possible, but they and others anticipate things will only get more complicated in the near term.

“2026 will bring with it a new set of EPR laws and recycled content laws,” predicted KDP’s Schwarze, “and they're going to be different than what we have right now.”